“Such miserable pirates are too sordid to engage a photographer to make a special series for them; they prefer to rob an already poorly paid class of men-men who have to depend for their living upon the sale of views taken during the short summer months.”

Most photographers today believe that the problems of image piracy began with the Internet in the 1990s and the switch over to digital in the 2000s.

That’s what I thought too — until this weekend when I was doing research for a book project on the archive site Canadiana.ca. I serendipitously came across some old copies of the Canadian Photographic Journal from 1894 and 1895. If you read about the problems photographers were facing with image pirates and with news organizations that took images without credit 122 years ago, it appears that things haven’t changed all that much.

MORE CONCERNING COPYRIGHT

WE have on former occasions tried to impress our readers with the vital importance of registering their copyright in photographs that are likely to prove of more than passing importance, and we published in a former number a concise article upon the method of securing such registration in Canada.

We have since received numerous complaints from subscribers who have been victimized by pirate publishers. One of these firms of pirates began by buying a few photograms of a prominent Canadian city at a cost of about twenty-five cents each and then published them as photo engravings in “Souvenir” form at about ten cents the book.

We do not mean to say the photograms thus collected at so little expense were by any means excellent views, and the reproductions were even worse, but still put upon the market at so low a price-they were sold and must have injured the sale of the original photograms.

We have no battle with publishers of these books so long as they pursue their business in a straightforward manner and give the photographers, whose works they appropriate, adequate remuneration and proper acknowledgment of authorship.

But we have no sympathy with the meanness of those marauding pirates who infest certain cities and rob hardworking photographers of the results of their labors. It is all very well for these people to say they bought and paid for the views they republish, we admit that they did so-but they did not thereby acquire the right to republish those views and sell them in opposition to their original authors.

Such miserable pirates are too sordid to engage a photographer to make a special series for them; they prefer to rob an already poorly paid class of men-men who have to depend for their living upon the sale of views taken during the short summer months.

These same parasitical publishers seem- to be imbued with a natural inborn baseness that prevents them from giving the men they rob credit for being the authors of the original photographs, whereas if they had the decency to publish the names and addresses of the photographers we might consider it in the light of a redeeming act of grace.

How often do we see even in the public press such titles as “Minne-haha Cathedral From a Photograph.”

Why are publishers so averse to give credit where credit is due? Is it because they are ashamed to publish the name of their victim, or is it because they fear he might be a gainer of some notoriety if his name was mentioned?

If newspapers are mean enough to take the liberty of appropriating men’s work and publishing it, they should not be too mean to advertise him by mentioning bis name and address.

Since there is such a lamentable lack of honorable feeling among a certain class, the only remedy for photographers is registration of copyright and, again, we urge our readers, if they do not wish to, be at the mercy of copyists, to register each of their choice views.

We know that the Canadian Copyright Act is hardly in accordance with the requirements of photographers-the rates being (in their peculiar circumstances) especially high-but still registration is the only way of protecting individual interests.

In Great Britain there has been recently formed an active “Copyright Union” which is virtually under the wing of the Chamber of Commerce.

The active promoters of this union have our most hearty sympathies; they are doing a good work for our British brethren and deserve the undivided support of every photographer in the land. Canada has long been in want of such an active body to protect the interests of photographers.

We believe the time is now ripe for the formation of such a union here, and we believe the best expression of our sympathies with the organizers of the British union will be the formation of a similar body in Canada. We want an amendment to the Copyright Act an amendment that will be an equal gain to photographers and the treasury of Canada.

Individuals cannot secure this, a powerful combined effort can do so.

The active co-operation of all photographers is required to fight for that which is, according to the unwritten code of honor, their individual right.

A year later in May 1895, the Canadian Photographic Journal published this letter from New York City.

SIR, -At an informal meeting held by a number of representative photographers of this city, March 14, 1895, it was unanimously decided to issue the following prospectus to the prominent members of our profession, submitting the plan proposed therein to their earliest consideration, and requesting their immediate reply to same address, Committee of the proposed Photographers’ Copyright League, 13-15 West Twenty-fourth Street.

Art in photography is at last a generally acknowledged factor, and the productions of photographers have become the chief source of supply for the illustrations which fi1l newspapers and periodicals. Even the courts now recognize that fact and extend the protection of the copyright law to all such photographers as are artistic.

During the past ten years a vigorous battle has been waging between a few determined photographers on the one hand, and an indiscriminate host of lithographers and other pirates, on the other. The latter had become so used to appropriating without leave whatever they saw was good and original in photographic publications, giving in return neither remuneration nor even credit, and the results to them were so profitable, that the effort to break them of the pernicious habit was no easy matter.

On the contrary it developed rapidly into a serious and bitterly contested struggle.

Thus far each photographer has done his fighting, sing]e-handed, and generally against large and powerful corporations. In spite of this, however, the result has been almost uniformly a complete victory for the photographer, decision after decision being rendered in his favor by the courts, though often only after years of burdensome and expensive litigation.

In view of these facts and other reasons which follow, we deem it wise and expedient, at this time, to band our best men together, so, that in future a united front will be opposed to infringers of all kinds.

There have been many demands within the past few years for such a union, and we know of no question now rife in the fraternity in which a community of interests would be more desirable, mutual and in every way advantageous to us all.

Our proposition is that an organization (to be known as the Photographers’ Copyright League of America) be formed at once, and take upon itself, by means of an advisory committee to be elected annually, the prosecution of all infringers of the copyright works of any of its members, whenever a proper case for such prosecution is presented by him ; that it defray all expenses of same ; and that in return, so as to make it self-supporting, a fair percentage of all recoveries so obtained, be turned into the treasury.

Notes

This entry cross posted from my photography blog.

The nineteenth century definition of photogram is obviously different from today’s “image made without camera”. From the context it appears to refer to souvenir postcards.

In the nineteenth century, Canadians were encouraged to register copyright materials with the Department of Agriculture. Today, under the Berne Convention, Canadians don’t have to register, but can if they wish with the copyright office. However, unlike the United States, there is no requirement to file a copy of the work.

An online search has found no references to the Photographers’ Copyright League of America. It would be interesting to find out what happened to the organization.

The original copies of the Canadian Photographic Journal for May 1894 and May 1895 are available online. Full access to the Canadiana.ca archive costs $10 Cdn a month.

One has to note that despite the fact that magazine masthead shows a woman photographer with a camera on a tripod, the copy is somewhat sexist, referring to photographers as “men” and a “fraternity..”

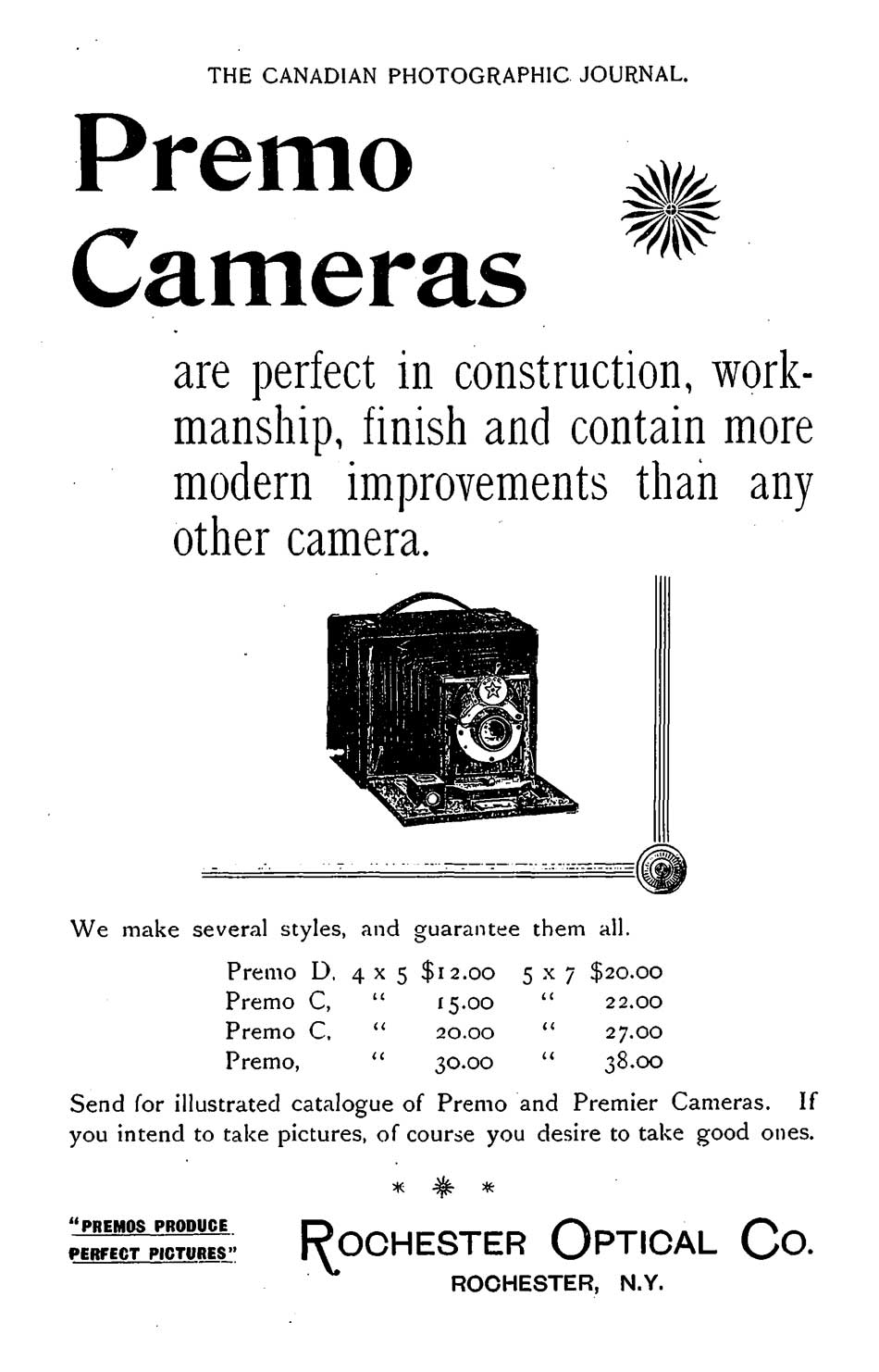

And now a word from our sponsor……the latest gear for May 1895 (ad in the Canadian Photographic Journal)