As a retired producer who worked at the national level at both CBC News and CTV News I was appalled at the superficial (to say the very least) coverage in English Canada of the shooting at a Quebec City mosque last night , January 29, 2017.

So were many people. The news was coming in on Twitter and Facebook, not television and along with the real news (and the fake news) there were complaints that neither CBC nor CTV had any coverage. The viewers were demanding television coverage from both the public CBC and the private CTV.

While Societie Radio Canada and its French language private competition TVA were live and in-depth, the CBC National broadcast on both the main network and News Network had nothing more than a minute of a phoner voice over. A disgrace for a national public news service.

At 11 pm, Pacific, that’s 2 am Eastern, CBC News Network went back to a canned documentary while BBC World devoted much of its newscast to the shooting.

This is the age of instant communications. Mobile phones. Text. E-mail. Twitter. Facebook.

It is obvious that in this age of 24/7/365 communications neither network news service has an emergency plan.

Probably in the view of bean counters and consultants news happens most often when there is a regular measurable audience and a newsroom is fully staffed (or as staffed as much as today’s budgets allow) and the new buzzwords like a “Hub” or a “Breaking News Desk” will always respond.

The Hub and Breaking News desks can only respond if there are warm bodies with their bums in chairs actually in the newsrooms.

Maybe the network news bosses should bring an old analog era procedure that actually got (real) breaking news on the air fast. It’s called a phone tree.

Back when I was starting in journalism 40 years ago, the days long before Breaking News became nothing more than a marketing gimmick, there were emergency plans and procedures and when the fertilizer hit the fan you learned quickly how those procedures worked. Even if you were a lowly editorial assistant (a job that no longer exists) almost all alone in the newsroom.

These long forgotten procedures were created (I was told at the time) when the Greatest Generation returned from service in the Second World War to begin or resume careers in journalism and they damn well knew what an emergency or breaking news really were.

So here’s how I learned my trade back then:

On September 28, 1978, it was just after one in the morning at the old National Radio Newsroom on Jarvis Street in Toronto. The evening staff had gone home. There was a writer for the hourlies for western Canada. The late Doug Payne producer of the World at Eight was preparing the show. His writing and producing staff would not be in for a couple of hours. I was the editorial assistant. It was still the days of clattering teletypes in a side room. Nothing had moved on any of the teletypes for an hour. Nothing. Then suddenly the Reuters machine literally went nuts. Normally five bells on an old teletype was a Bulletin. A Flash was seven. This time the machine rang 28 bells. (I saved the carbon copy and counted them later) The new Pope John Paul I was dead. (He had been in office just 33 days).

I was stunned for a few seconds, then ripped the paper and ran over to Doug.

Doug knew what to do. He knew the phone tree.

First I was to call the then senior assignment producer, Bob Dowling.

Second and only after I had called Dowling, who could start getting the foreign desk and reporters mobilized, I was to call the then managing editor Eric Moncur.

Doug and the writer under CBC procedure at the time (not these days) waited for the CP/AP confirmation. They then prepared the network bulletin and after that the last two hourlies to the west.

Doug told me that once I had called the boss, I was to call in all the morning staff for both World at Eight and Hourlies, starting with producers and senior technicians, then writers and junior technicians. Overtime was no problem. The early morning EA didn’t answer (I later learned he was spending the night at his girl friends’) so I was told to call in the mid-morning EA. Doug then told me to call Frans, the nearby all night restaurant and order breakfast to go for 30 people. As soon as the mid-morning EA got in, he was sent out again in a taxi, with an envelope full of cash to collect the breakfast. (Eggs, bacon and sausage).

I was also fielding calls from the public (including an assistant to the Archbishop) who had direct lines numbers to the newsroom in something called a Rolodex. (In the first round of many budget cuts the overnight switchboard operator had been let go a few weeks earlier)

In Toronto, noise bylaws forbade the Catholic Churches’ bells from ringing until 7 a.m. But as the World At Eight went to Atlantic Canada, the listeners could hear LIVE, those bells ringing.

A year later, on November 10, 1979, it was a deadly Saturday night. There were two people in the radio newsroom, myself and the hourly writer. Down the hall a producer for Sunday Morning was putting the last minute touches on a doc that was to air that morning.

It was five minutes to midnight. Five minutes until the switchboard closed. It was then the phones started to ring. There had been some kind of huge explosion in the west part of Toronto. At midnight those calls stopped.

Those calls were enough for me to follow the phone tree procedures and call Bob Dowling. It was soon after that that news staff began calling on direct lines, not just from the west end but even from high rises in downtown Toronto, telling me there were huge flames in the west.

A Canadian Pacific train had derailed in Mississauga at 11:53. So those warning phone calls from the public had come almost instantly. Dowling went through the phone tree, calling in staff and alerting reporters. Then he called back and ordered me, the most junior person and the available warm body to get out to the scene until a national reporter could relieve me. There was a problem, the weekend CBL (local Toronto radio) reporter had taken the staff car and he couldn’t be contacted. So Dowling authorized a technician who should have gone off shift to drive me on overtime to the scene in his personal vehicle.

As soon as we got on the Gardiner, we could see the flames reaching 1500 feet into the air; we eventually got to the scene, and (in those days) were waved through the police barricade to a parking lot designated for the media. Even for the TV people who were also arriving this was long before the days of easy live coverage. But there was a quick police briefing within a half hour or so. Soon after the briefing, a national reporter arrived, so the tech and I drove off to find a place to file. In those days that involved taking a phone apart and using alligator clips to send audio from a tape recorder back to the newsroom. Then, the tech and I went to a mall that was an evacuation centre that was already filling up, for interviews. We were back in the newsroom by 5 am, which by that time had all hands on deck.

On August 19 1991, I was a writer at CTV News in this case the Sunday news with Sandie Rinaldo. It was a dull, routine Sunday night with (as far as I remember) until about 11:25 when once again it was Reuters, this time on a green CRT screen tied via some badly written software to a mainframe, that sent the Bulletin that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union had announced that Mikhail Gorbachev was no longer in office. It was the infamous August coup. I called the show producer Jennifer Harwood (now a CBC News manager) and read her the bulletin.

Normally on a Sunday night after the control room told us “tape is good” everyone would go home. The control room called, tape was good, but there was no call back from the producers saying they could go home. Everyone was reading the wires. Control room called back, “What is going on?” So I told them and told them to stand by. The coup meant that there had to be a whole new show with real breaking news put together in now less than half an hour.

At the same time, the CTV phone tree was activated. Calls were made to then CTV VP of News Tim Kotcheff and senior assignment editor Dennis McIntosh. The midnight show to Central Time Zone made it to air (of course) and then after that show was off the air; there was a full network special report aimed mostly at the eastern, Atlantic and Newfoundland stations that had already broadcast the original newscast.

That’s how the system was supposed to work. That’s how it worked at both public and private networks when the networks had executives and managers who knew what they were doing.

My sources tell me that at CBC there is minimal staff assigned to the Sunday National (unlike the old days when the Sunday National was a flagship that led the rest of the week.) and even the English Montreal local CBC newscast was a disaster.

This news disaster is the result of decades of budget cuts, staff reductions and misleading viewer analytics that say it isn’t worth money investing in weekend coverage. At CTV I suspect that the parent company Bell Media has no real interest in actual news coverage in a demographic low point. CBC lost its way as a public broadcaster years ago, with too many managers and too many managers who know nothing about broadcasting and don’t consider news apart from marketing it.

The CBC now has version 5.0 or higher of a so-called digital strategy. The news of the shooting was on Facebook and Twitter, not much even on CBC.ca (they can’t do much if there’s one writer and no reporters on scene to feed information) and everyone in English Canada was waiting for CBC to go live with real reporting. It never happened.

In these days when all the media is in deep trouble, there are some things you can’t fix.

But one thing can be fixed. Remember the Greatest Generation.

Remember the old Journalism School 101 adage. Never Assume.

Never assume that news is going to break when you’re expecting it.

Come up with a real 21st century emergency plan and bring back that old analog frigging phone tree system and when there is real breaking news get it on the air and out on digital and social media whether it’s on Wednesday afternoon or Sunday night. Accurate and fast. Accurate is crucial in the age of fake news on social media.

Here’s what John Doyle of the Globe and Mail says

John Doyle: Lack of TV news coverage of Quebec City shooting a huge broadcast failure

(In the first upload, I mixed up east and west. Mississauga is west of Toronto. It has been corrected)

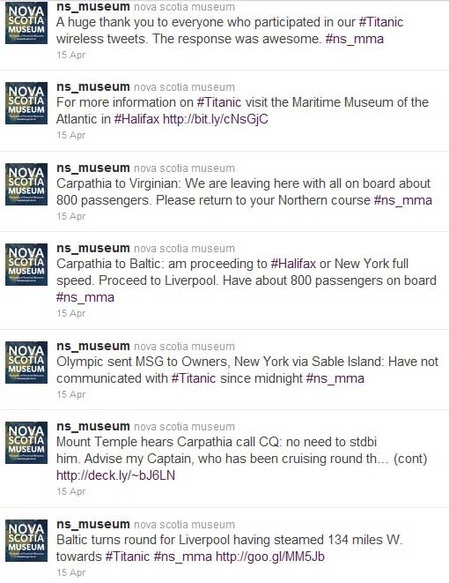

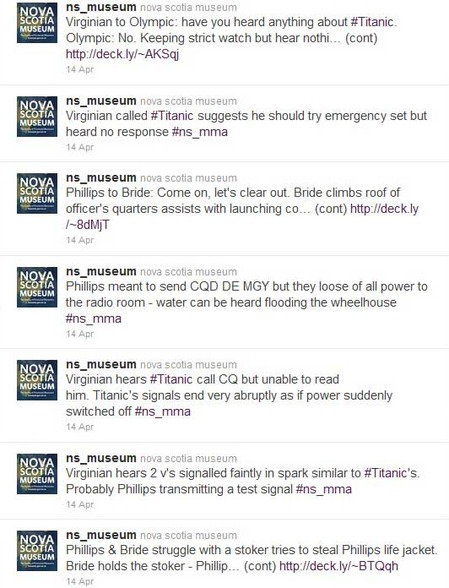

One last note, During the CBC lockout, I wrote a blog about the Titanic’s musicians and how badly they were treated by the White Star Line,. See

One last note, During the CBC lockout, I wrote a blog about the Titanic’s musicians and how badly they were treated by the White Star Line,. See

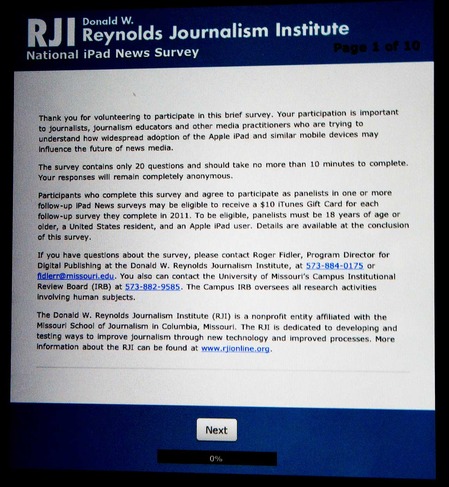

desperate media companies offers they cannot refuse, demanding that they charge for content on the Ipad so Apple can get its 30 per cent cut, content that Apple says it can censor at will. Of course, there were dozens of tablets at the 2011 Consumer Electronics Show, but the question is how many of those tablets will survive the evolutionary competition and whether or not one tablet succeeds by giving the media companies a way of saying no to the godfather from Apple.

desperate media companies offers they cannot refuse, demanding that they charge for content on the Ipad so Apple can get its 30 per cent cut, content that Apple says it can censor at will. Of course, there were dozens of tablets at the 2011 Consumer Electronics Show, but the question is how many of those tablets will survive the evolutionary competition and whether or not one tablet succeeds by giving the media companies a way of saying no to the godfather from Apple. In physics,

In physics,  system, was already working on the development of the

system, was already working on the development of the

.

.

Some corporations never learn. Now we see overuse of the Twitter alert for routine news stories, even when the same news organization has Twitter accounts for the routine. That overuse only diminishes the brand and all the public has to is unfollow the overused alert.

Some corporations never learn. Now we see overuse of the Twitter alert for routine news stories, even when the same news organization has Twitter accounts for the routine. That overuse only diminishes the brand and all the public has to is unfollow the overused alert. One aggressive invasive species is Wikileaks. Wikileaks enters that investigative niche largely abandoned by the increasingly too specialized apex media species. Like other invasive species, Wikileaks, also disrupts the ecosystem. Wikileaks is not the same kind of species Again imagine a tall and solid investigative fir tree, now old and rotten. Wikileaks, perhaps, it is too early too tell, is the media ecosystem equivalent of kudzu or purple loosestrife that fills the place emptied by that fallen tree.

One aggressive invasive species is Wikileaks. Wikileaks enters that investigative niche largely abandoned by the increasingly too specialized apex media species. Like other invasive species, Wikileaks, also disrupts the ecosystem. Wikileaks is not the same kind of species Again imagine a tall and solid investigative fir tree, now old and rotten. Wikileaks, perhaps, it is too early too tell, is the media ecosystem equivalent of kudzu or purple loosestrife that fills the place emptied by that fallen tree.

time again by know nothing managers to attend a session with an expensive consultant only to find out that our staff usually knew more than the consultant. In 90 per cent of cases, consultants are a waste of time and money. In ecosystem terms, consultants are like epiphytes, air plants, that look good, often with pretty flowers, on a tree branch or trunk but are essentially parasites, living off the tree itself. If you want your staff to listen to the latest guru, pay for them to attend a conference where they can get the same canned speech at a much lower cost, and may find an even better idea in a small seminar or a corner booth.

time again by know nothing managers to attend a session with an expensive consultant only to find out that our staff usually knew more than the consultant. In 90 per cent of cases, consultants are a waste of time and money. In ecosystem terms, consultants are like epiphytes, air plants, that look good, often with pretty flowers, on a tree branch or trunk but are essentially parasites, living off the tree itself. If you want your staff to listen to the latest guru, pay for them to attend a conference where they can get the same canned speech at a much lower cost, and may find an even better idea in a small seminar or a corner booth.

.

.